Being there: American researchers extol benefits of returning to China

- Between Covid-19 restrictions and US-China frictions, trips by academics and think-tankers have dropped off sharply

- But three who have made recent extended trips confirm that there’s no substitute for in-person interactions

After three attempts and eight months of upended plans, Scott Kennedy finally returned to Beijing in September, determined to rejoin Chinese counterparts that he had not seen in person since 2019.

Kennedy, a senior adviser at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies in Washington and a frequent consultant to the US government, has travelled to China for over 30 years – making six trips in 2019 alone.

He studies the gap between Chinese economic policy and its commercial performance, which requires on-the-ground research. But the purpose of his six-week trip this time was not just to collect data.

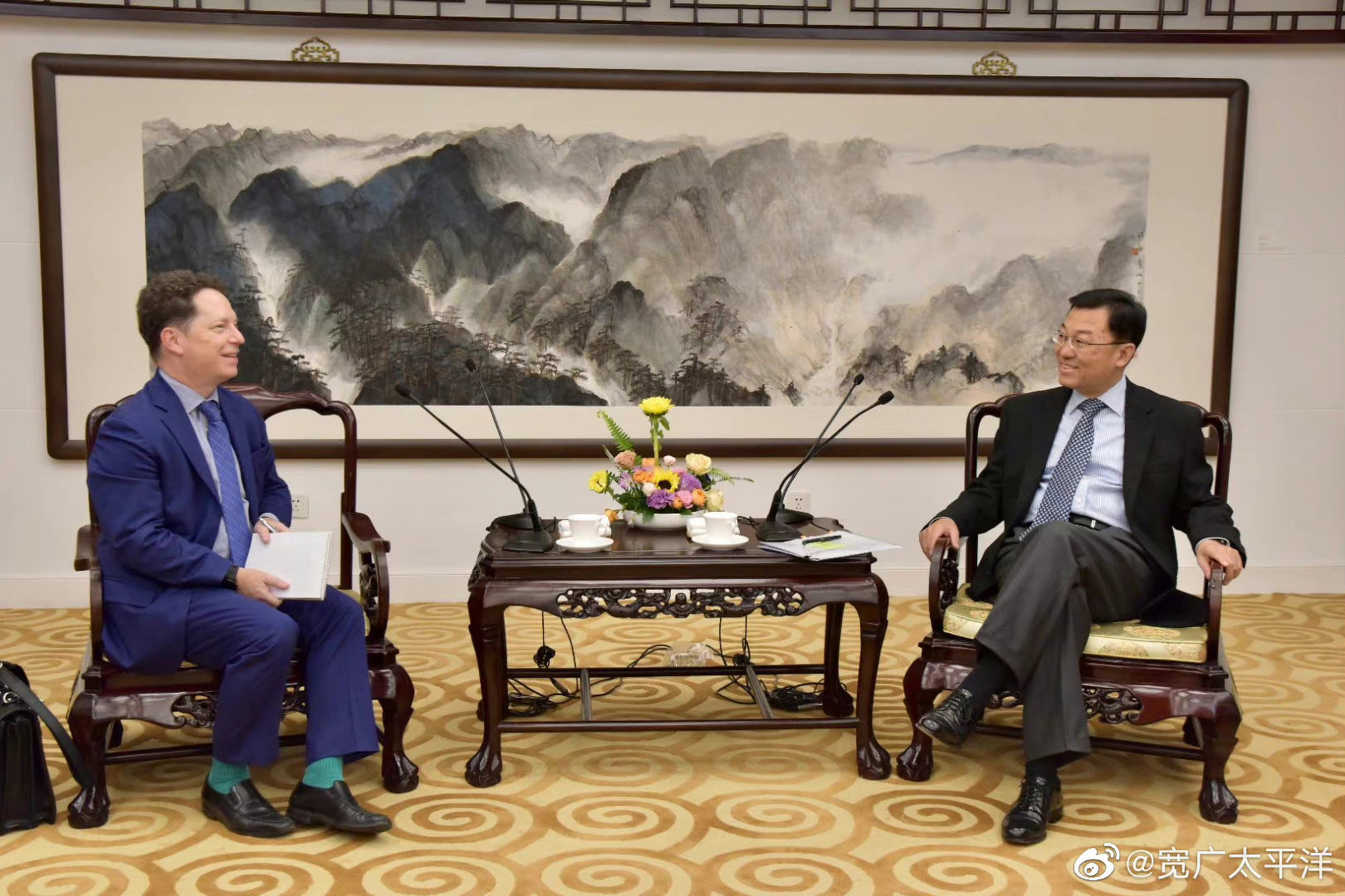

Part of a reciprocal swap with Wang Jisi, a professor of international relations at Peking University, Kennedy’s return also emphasised the irreplaceable value of in-person scholarly exchange with China.

Almost three years after the pandemic first spread and amid China’s zero-Covid policy as well as a deteriorating US-China relationship, fewer than 400 American students are in China, according to estimates Kennedy was given in October – a sharp contrast from 2018, when China was hosting more than 11,000.

Despite some business travellers resuming trips to China, few American academics have made their way back – deterred by quarantine rules and the unpredictability of China’s Covid policy.

Canadians Kovrig and Spavor freed by China arrive home

Even so, a trickle of long-term China watchers like Kennedy have found their way back in recent months. Deborah Seligsohn, a political scientist at Villanova University, and Denis Simon, professor of China business and technology at Duke University – both with decades of experience travelling to China – made trips in mid-October as the 20th Communist Party congress was starting. Simon returned to the US in mid-November; Seligsohn remains in China.

Their trips all relied on Chinese state hosts – including Peking University and the Chinese Academy of Science and Technology for Development – and tremendous investment of effort and expense from the Americans’ end to apply for approval, secure flights and spend weeks in quarantine.

Despite the logistical hurdles involved with their returns – which for Seligsohn and Simon each involved 17 days of quarantine – the three researchers all said their trips were worth the hassle.

“It was a very fruitful visit. I had some of the most frank talks I’ve had in China across 40 years,” said Simon, who works on US-China science and technology cooperation.

“I was surprised that people would be willing to see me,” Kennedy said. “I was told by some that because of political tensions that no one would want to see an American but … I was impressed by the low refusal rate for meetings.”

Seligsohn, who studies US-China climate relations, had a similar experience, though she did not meet with any officials. “Because of all of these Covid restrictions, people are way more interested in getting together than was the case when visitors were a dime a dozen.”

“In that regard, it’s more like the old days,” Seligsohn said, recounting experiences from the mid-1980s when American engagement with China was just beginning in earnest.

Simon, who until 2020 served as the executive vice-chancellor for Duke Kunshan University in Suzhou, said that “the Chinese side went out of their way to be accommodating”.

The fact that I was in the country helped contribute to a sense that everything could go on the table

“They were well informed about the state of the relationship but they also missed the regular interactions with foreign scholars and friends.”

“There is a tremendous amount of energy to restore the vibrancy in the Sino-US relationship in science and technology and education,” he said.

All three scholars described discovering narratives that they did not have access to through online sources, despite following China very closely in their work.

“I don’t think you can understand what it’s like here during Covid if you don’t experience it yourself,” said Seligsohn, who served as a science counsellor at the US embassy in Beijing from 2003 to 2007.

Simon said he now had a better sense of why China’s zero-Covid policy persisted: “There’s a real sense of obligation to the country and society among at least the government people that I was with, many of whom I know for a long time.”

Kennedy also found his experience with Covid in China enlightening. “The Covid conversation sounds a lot like the conversation in the United States and I didn’t expect that because China’s Covid policy is so different from the US’,” he said.

On a range of issues, from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine to China’s ability to overcome American technology restrictions to the nation’s future, Kennedy said he found perspectives that outsiders did not usually have access to.

“Some people in China are confident about their future … but if you just read the media, you’ll come away with one very simple dark view.”

Simon and Kennedy also noted the unique access to the Chinese policy process that being in the country provided, which Kennedy said was crucial to assessing where China was going and avoiding unnecessary escalation.

“[In person,] you learn more clearly about the intellectual origins of what is official policy, as well as the dynamics of how that policy came into being … and what they’re trying to communicate through their policies,” Kennedy said.

“It’s hard to know without being physically in China what the rank-and-file people know,” Simon said.

China-based interlocutors were already highly cautious regarding interactions with outsiders, the scholars noted, and the online environment accentuated these concerns.

Many people feel naturally hesitant when meeting strangers, but “if you’re online, it’s going to be even worse, because anybody can be watching, potentially”, Kennedy noted.

Simon agreed, adding that “the fact that I was in the country helped contribute to a sense that everything could go on the table”.

In-person interactions also allow for wider-ranging conversations.

“You don’t have to have as much purpose for all of them. You can just get together and catch up,” Seligsohn said.

Like Kennedy, Seligsohn and Simon returned for research purposes but also wound up with the difficult task of interpreting Washington’s China policies for their Chinese interlocutors.

“They really do want to figure out what the formula is to get things back on track,” Simon said, referring to conversations he had with Chinese science and technology officials.

The scholars said that the limited travel between the two countries had led to missed opportunities and had deleterious effects on mutual understanding. And the future remains uncertain.

Despite his positive interactions, Kennedy said he found “more scepticism, less willingness, less curiosity” from the Chinese side about engaging with the West. He attributed the Beijing’s growing debate over the value of foreign engagement partly to China’s economic success.

Some Chinese wariness may be driven by perceptions of Washington’s motivations. “Some people may be cautious because they feel like the US government is an antagonist and anything they say can and will be used against them,” Seligsohn said.

But, Seligsohn said, distinctions were still made between officials and US citizens. “A lot of people here say we like Americans, we just don’t like your government,” she noted.

Neysun Mahboubi, a research scholar at the University of Pennsylvania’s Centre for the Study of Contemporary China, said that despite their limited number, these initial post-pandemic scholarly exchanges remained beneficial to dealings between the US and China.

“Given how toxic the bilateral relationship is right now, having even just a little bit of the kinds of exchanges we used to have is clearly positive,” he said.

American scholars who made regular trips to China played a role in disseminating a “real sense” of what was happening in the country, Mahboubi said, adding that such trips were important not only for the intrinsic quality of scholarship but also for maintaining a balance to the bilateral relationship.

“It’s very sad to contemplate that the role of this entire universe of exchanges before is now being asked of these two or three individuals.”

Mahboubi said that a unique combination of factors had to fall into place for these trips to happen and that crucial to these scholars’ ability to conduct trips like these were the networks they developed over decades of travel to China, he said – deep connections that were hard to form online.

“If younger generations are not able to travel to China, it will be impossible for them to develop those kinds of resources, and that will have deep reverberations for the future of the bilateral relationship,” Mahboubi said.

‘Too weak’: Chinese scholars warn of knowledge gap with American peers

Wang’s visit in February was received “like a glass of cool water in a desert” in Washington, Kennedy said, promising more exchanges in the near future.

The resumption of academic exchange is one of several lines of defence to repair the relationship. This week, the Wall Street Journal reported that a Chinese delegation of policy advisers and business executives met their US counterparts ahead of the meeting in Indonesia this month between US President Joe Biden and Chinese President Xi Jinping.

“The biggest cost of Covid is really the empathy gulf between the two countries,” said Craig Allen, president of the US-China Business Council, who also just returned from a trip to China. “And that’s not a healthy situation for the world’s top two economies.”