(RNS) — Any woman paying attention to Christianity and politics in the U.S. has been left a little breathless this summer. No single ruling from the U.S. Supreme Court surprised me, but the rapidity and scope of the decisions were breathtaking: The justices legitimated public funding for religious schools; relegated complaints about coercive public prayer to the churlish fringe; and tossed out half a century of rulings that keep old men from dictating how we use our private parts.

If it seems the church-state line has suddenly become a dotted one, you are not imagining things. In these recent rulings, the court has accommodated a particular form of religiosity. But the federal government’s shift has been going on for decades, in an evolution that is less pro-religion than anti-government spending on social services.

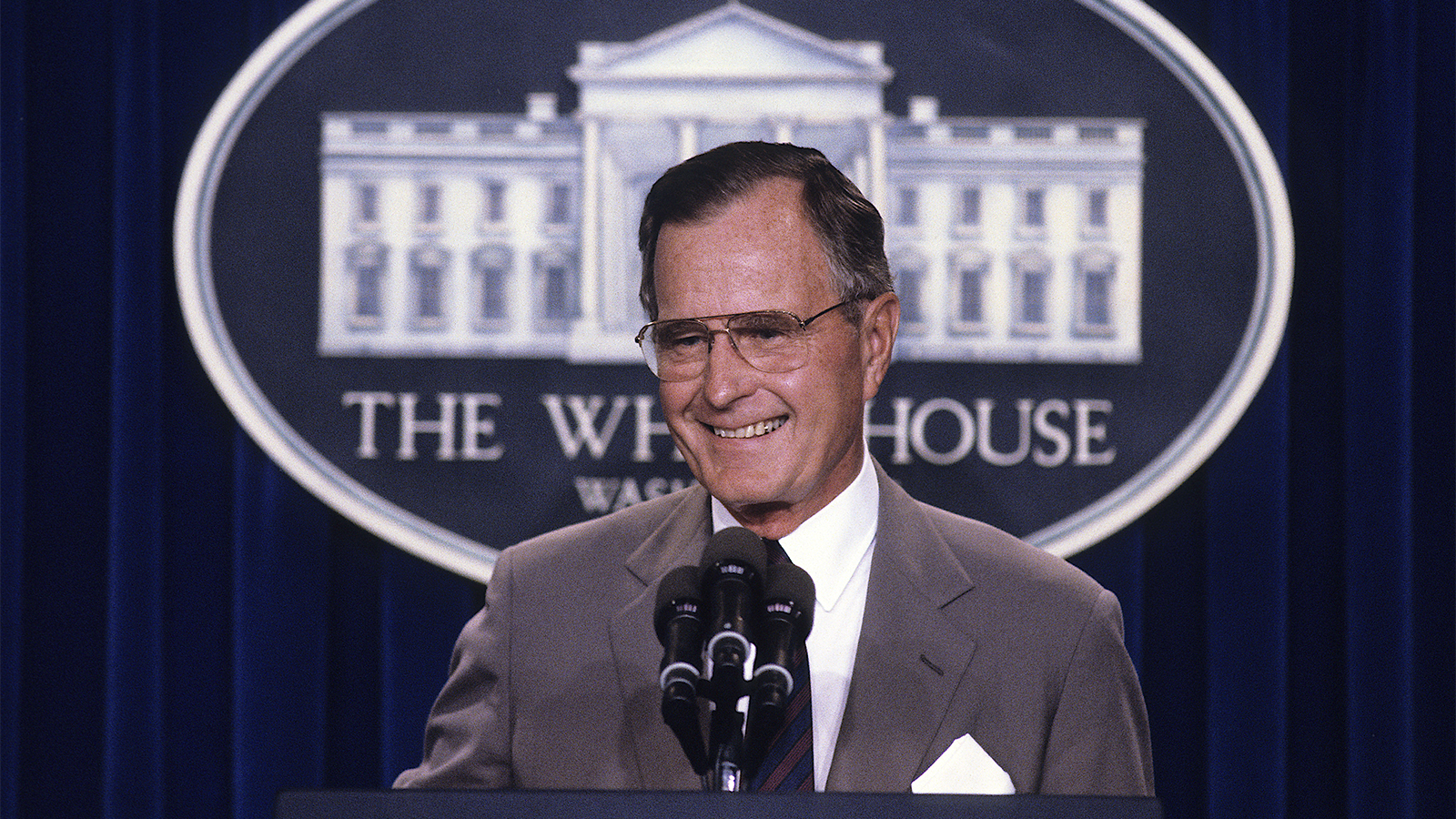

I arrived in North Carolina to teach at Duke Divinity School in 1999. This was the heyday of “Charitable Choice,” a program the Clinton administration had inherited from George H.W. Bush, who used the literary conceit of “a thousand points of light” to foster an image of faith-based organizations helping their neighbors in need. President Bush had a vision of Americans helping Americans, as they had in a fabled past before the federal government had intervened with food programs and low-cost health care for the young, old and most vulnerable.

It was Bush’s avuncular, conservative Episcopalian version of the more draconian ethic of the Reagan administration, which for the previous eight years had defunded the most basic of social goods, including many that serve children.

As science journalist Olivia Campbell noted: “A million children lost reduced-price school lunches, 600,000 people lost Medicaid, and a million lost food stamps. The Women, Infants, and Children program could only serve a third of those eligible. WIC provides low-income pregnant women and children with formula and healthy food staples.”

President George H.W. Bush responds to questions during a news conference at the White House in 1990. Photo by Mark Reinstein/MediaPunch /IPX

In the subsequent decades, answering the younger President Bush’s “compassionate conservatism” and similar such taglines, people in religious communities stepped into the breach left by the federal government to serve their neighbors with charity. After-school, in-school and before-school tutoring programs, shelters for people without homes, interview-suitable dresses for women newly released from prison were all provided by organizations trying to light the void.

Ever since, African American, white and Asian clergy have called on volunteers to fill in where hard-won, truly trained and capable service-sector professionals have been defunded out of their own vocations. Church people may have been light, but we have also been scabs.

This decades-long effort has been bolstered by a theology that makes the replacing of government services with faith-based helpers seem simply normal. Major funders have been active in this effort to give intellectual support to this shift from public funding to nonprofit, faith-based initiatives. I took part in a ”Project on Lived Theology“ at the University of Virginia that assessed faith-based models for community engagement.

Yale Divinity School has received decades of funding for various “faith and culture” projects to focus graduate students and their mentors on ways that Christianity serves the public good. The Templeton Foundation has funded efforts across disciplines and universities to promote the notion that religiosity itself leads to better individual and public health.

My own Duke Divinity School has received steady Lilly funding to link the words “thriving,” “faith” and “community.”

At times such programs have legitimated the “points of light” political reality by focusing attention on the ostensible goods offered by faith communities — tangible goods like back-to-school backpacks and less tangible goods like “reconciliation” or “resilience.” These programs burnish a morally and fiscally reactionary argument against government funding and regulation of social services. After all, don’t the women at your local church know better what their community needs than some government bureaucrat?

People work together organizing donations at a food bank. Photo by Joel Muniz/Unsplash/Creative Commons

Anyone who contested this rationale would be shut down by those Linda Greenhouse has helpfully termed ”grievance conservatives.” There are people who are against religiosity itself, these supposed victims of secularization say, and they must be countered by way of public witness against a “ban” on religion.

But one needn’t be a small-government conservative to buy into the trend. Many people of faith, out of a desire to remain relevant and, often, to serve their neighbors, find these schemes to make faith seem socially useful alluring.

Colleagues here at Duke, worrying about the secularization of daily and common life in the U.S., have said words like, “We don’t want to become Australia, where Christianity is seen as a quaint relic.” Or “Look at what has happened to churches in England, as they rely only on their past, with barely enough people left to sing a hymn on Sunday!” These are people who contribute to National Public Radio, who watch MSNBC, not Fox News; their anxiety about religious authorities losing cultural influence is palpable. When David Brooks opines about the loss of morality, they nod knowingly.

The whole shift from public to private, from material to spiritual, may appear not only normal, but part of a morally good, grand adventure.

Amy Laura Hall. Courtesy photo

In fact, it has been part of a grand strategy aimed at undoing the government’s involvement in what was once known as the Great Society. And it worked.

(Amy Laura Hall is associate professor of Christian ethics and of gender, sexuality and feminist studies at Duke Divinity School. She is the author, most recently, of “Laughing at the Devil: Seeing the World With Julian of Norwich.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)