China on a mission to turn ‘junk’ patents into treasure

- As part of its drive to achieve technological self-sufficiency, Beijing is overhauling its system of reward for patent filing

- Chinese universities file many more patents than their US counterparts but only a fraction are converted into commercial applications

Shenzhen University, a relatively young educational institution at 38 years old, filed the third-highest number of international patents in the world last year, beaten only by the University of California and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Its 252 patent filings were more than Johns Hopkins and Harvard combined, the WIPO data showed.

The latest five-year plan lays out a strategy to unleash the value of this untapped research by enhancing its use while directing new R&D efforts and resources more efficiently towards market demands.

Lacklustre conversions

China’s National Audit Office said last year that government R&D spending converted poorly to commercial applications, with only 8.4 per cent of patents owned by universities and research institutes transferred or licensed for commercial use.

Among the 20 randomly audited university-affiliated science and technology parks, two had failed to commercialise any of their research output for more than a decade.

Lei Chaozi, the education ministry’s director general of science and technology, said in late 2019 that while the top Chinese universities had five times the patents of their American counterparts fewer than 10 per cent were converted to commercial applications, compared to 40 per cent in the US.

Veteran China patent expert Elizabeth Chien-Hale, who co-authored a book for the American Bar Association on commercialising intellectual property rights in China, said commercialisation had been limited “because the quality of the patents was lacking in the past”. Government restrictions on technology transfers posed another hurdle for high-quality inventions, she said.

China encourages its universities to take initiative in international science and tech

Another factor was the lack of good data on the value of Chinese patents, compared to the US where such information was readily available from licensing agreements and legal cases, said Chien-Hale, who is a partner at boutique international law firm Appleton Luff.

“In the US, a patent is a commodity. There is a price tag on it. But in China, a patent is not a commodity on its own. It is part of a technology transfer transaction. The value is just so much more amorphous because of that.”

In China, she said, “the damages awarded are too low, the commercial transactions are not transparent, and a lot of commercial transactions are not really about the money or the value – they don’t just pay you for patents, they do technology transfer, you may pay for incubation, the land, the connection”.

Who files junk patents, and why?

In his 2019 speech, Lei said too many patents were filed by Chinese universities to meet performance assessment targets for academic staff and their research projects.

The costs of filing and maintaining these patents are financed by government budgets, sometimes even coming with subsidies to researchers as rewards. But few were actually filed for the protection of inventions or technological discovery, the education official said.

Denis Simon, former executive vice-chancellor of Duke Kunshan University in the eastern province of Jiangsu, agreed that overemphasis on patent numbers had been a source of so-called junk patents, with no commercial value.

“The problem is that because everyone is so patent-oriented … a lot of the patents filed would never see some commercial light. People use [patents] as a metric to advance their academic careers but there was never any attempt to look at the quality of the patents,” he said, adding that the situation was similar at state research institutes.

“The connection between patents, profitability and commercial performance has not been there … They may raise the number of patents, but the reality is the patent and commercialisation of R&D has almost no connection. That is the big challenge for China,” said Simon, who is now a China business and technology professor and senior China affairs adviser at Duke’s main campus in North Carolina.

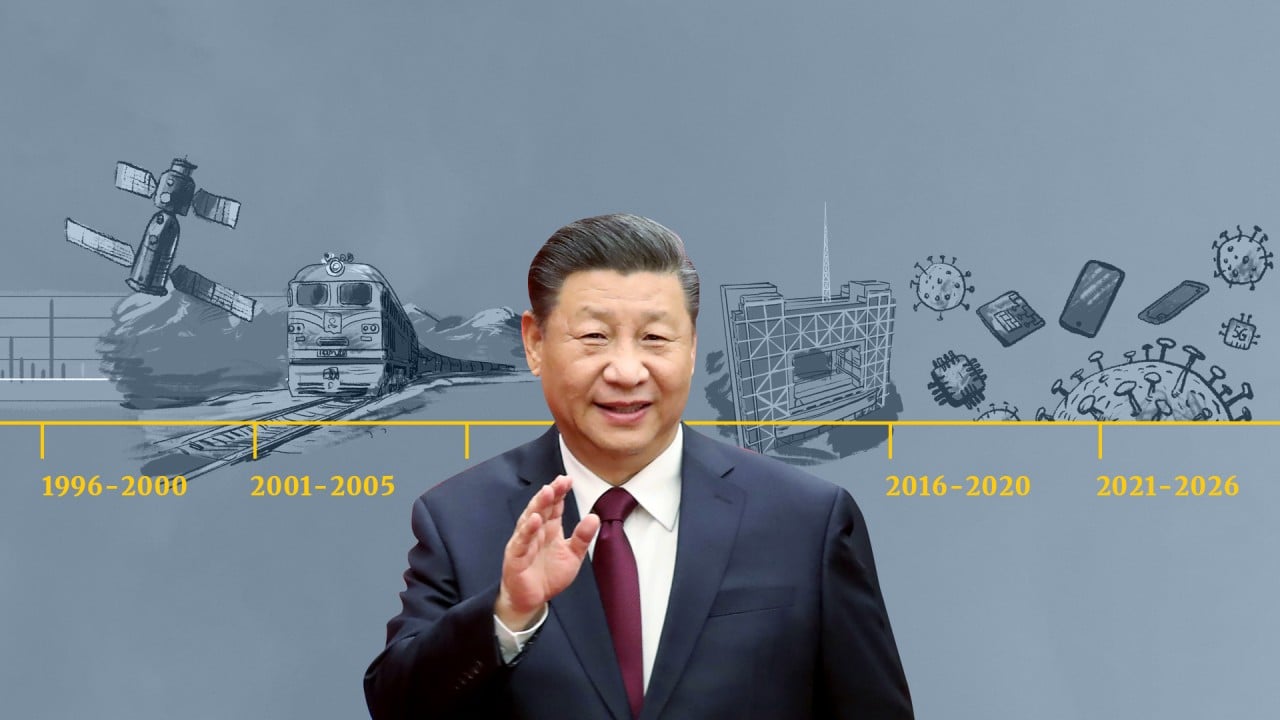

Chinese President Xi Jinping says intellectual property protection is key part of country’s development plans

Another problem faced by Chinese universities was a lack of IP management and intelligence before committing to research projects, Lei said, adding that their knowledge transfer offices were too small, often with two or three staff in contrast with dozens in their European and American counterparts.

Shenzhen University, for instance, has a professor and a team of three staff members overseeing the school’s intellectual property management and conversion affairs at its department of science and technology, according to its website.

Simon said Chinese universities’ past reliance on science and technology parks and incubators to commercialise their research results also proved inefficient, citing a conflict between academic and business goals.

“I think the example of Silicon Valley and Stanford University in the United States somehow has [been] exaggerated to some degree in China. You have lots of incubators all around the country, and lots of technology parks, but many of those have become like real estate investments,” he said.

“The incubator’s job is to graduate [start-ups] … but what you find in many Chinese incubators people never leave. They never graduate.”

But some intellectual property experts said the level of commercialisation for university patents might have been under-reported, especially for smaller schools that had privately entered into strategic R&D collaboration agreements with enterprises.

In these arrangements, they said, schools often applied for the patents while the businesses – which provided funding and know-how – had exclusive use of the patented technology without exposing their names to competitors.

Companies may also file for junk patents to qualify for subsidies and other preferential policies, according to industry insiders, in response to years of preferential government policies towards “high and new technology enterprises” (HNTE). This includes a corporate income tax rate of 15 per cent, compared to the standard 25 per cent.

China’s plan to boost innovation and what it could mean for research in Greater Bay Area

Local governments, including Jiangsu’s, also offer up to 3 million yuan (US$458,000) in subsidies for selected HNTEs that are preparing to list on the innovation board, while other authorities reward the filing of international patents with subsidies which are more than enough to cover the administrative costs, according to experts on Chinese patent policy.

A report by business media group Caixin last week revealed how a Guangdong-based intellectual property agency grew quickly by selling clients packaged patents it claimed would help them secure HNTE status and reap preferential treatment.

“There are inventors who benefited from these [preferential] policies, but there are also a lot of abuses. That is why the number of Chinese patents has exploded for a period … because some individuals and businesses made money by filing patents,” Chien-Hale said.

Quality, quality, quality

According to Chien-Hale, the “junk patents” phenomenon was raised as early as 2005 by then-intellectual property regulator chief Tian Lipu, but Beijing only recently began taking serious measures against the problem.

Communist Party journal Qiushi published two articles in February on the subject, one featuring President Xi Jinping and the other China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) commissioner Shen Changyu. Both talked about the need to raise the quality of China’s intellectual property.

“They are now concerned with the quality, quality, quality of the intellectual property being generated and they are not so much concerned with the quantity of patents or the quantity of copyrights,” said Simon, of Duke University.

“They really want to see what can be transformed into real commercially viable research output.”

China fails to meet research spending goal but aims to double efforts in applied research

“China has been notorious for having too many junk patents,” he said. “The IP authorities in China are making a sustained effort to clean up the entire patenting landscape.”

In its latest five-year plan, Beijing said it would optimise its policy of rewarding patent filings and implement a performance appraisal system to provide better protection and incentives for high-value patents.

Last month, the CNIPA went further, saying it would cancel all subsidies for intellectual property filings while pledging to crack down on junk patents and investigate irregular patent applications.

The Chinese patent office released a joint directive this month with the country’s top science and engineering academies to introduce a new vetting protocol to improve the gatekeeping of government-financed patent filings, along with other reforms in measuring researchers’ performance and utilisation of their research findings.

Simon said Beijing was also delegating more autonomy to Chinese universities in the handling of their intellectual property, an approach similar to the 1980 Bayh-Dole Act in the US – a landmark legislation that spurred inventions out of the lab and into commercialisation by allowing universities to retain title to government-funded inventions.

China’s education ministry said last month that one of its 2021 priorities was to accelerate the commercialisation of university research.

The government will strengthen its guidance to universities about the management of intellectual property and promote the development of knowledge transfer offices in colleges. It will closely work with universities on pilot reform schemes to grant researchers ownership of their inventions and discoveries.

Chien-Hale said local governments were also implementing plans to push for higher levels of commercialisation.

“The commercialisation gap and its problems will go away if China is able to prove to the world the high innovative contents of its technologies, and if the government will relax the standards for exporting technologies,” she said.