At first glance, the landscape of evangelical megachurches looks like a man’s world. Almost all of the largest churches in America are headed by men. Women make up the majority of churchgoers, but men look like the leaders and the stars.

But Kate Bowler sees powerful women hiding in plain sight. In her new book The Preacher’s Wife: The Precarious Power of Evangelical Women Celebrities, Bowler argues that evangelical Protestant women—conservatives in particular—have carved out extraordinary influence for themselves nonetheless. The cohort Bowler describes includes many women married to famous pastors and some who are pastors themselves. But it also includes independent speakers and authors like Beth Moore, Jen Hatmaker, Joyce Meyer, and others who have made their careers in the vast network of conferences, cable television, nonprofits, and church committees that makes up the lucrative and largely conservative world of “women’s ministry.” I spoke with Bowler, a historian at Duke Divinity School, about how these women became household names within evangelicalism despite being denied access to most routes to institutional power. This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Ruth Graham: One of the big themes of the book is that conservative Protestant women arguably have more cultural influence than women in more liberal Christian traditions. Was there a particular moment that sparked that realization for you?

Kate Bowler: When I was studying the televangelism scandals, I noticed that after so many men fell from grace, all of a sudden their ministries were much more willing to add a woman onstage as the co-pastor. In a way it was to provide cover to the man—to say, “Oh, don’t worry, he’s a family man. Nothing to see here. This is a ministry run with integrity.” I’m an expert in megachurches, but it took me a long time to realize that the very rise of megachurches had created a congregational form that required that women have power. When you have a church of a certain size, you now have a segmented demographic called “women,” and the dude can’t be in charge of that part without seeming weird. People then are married into these elaborate high-pressure jobs.

What happens when wives don’t have an interest or aptitude for that kind of work?

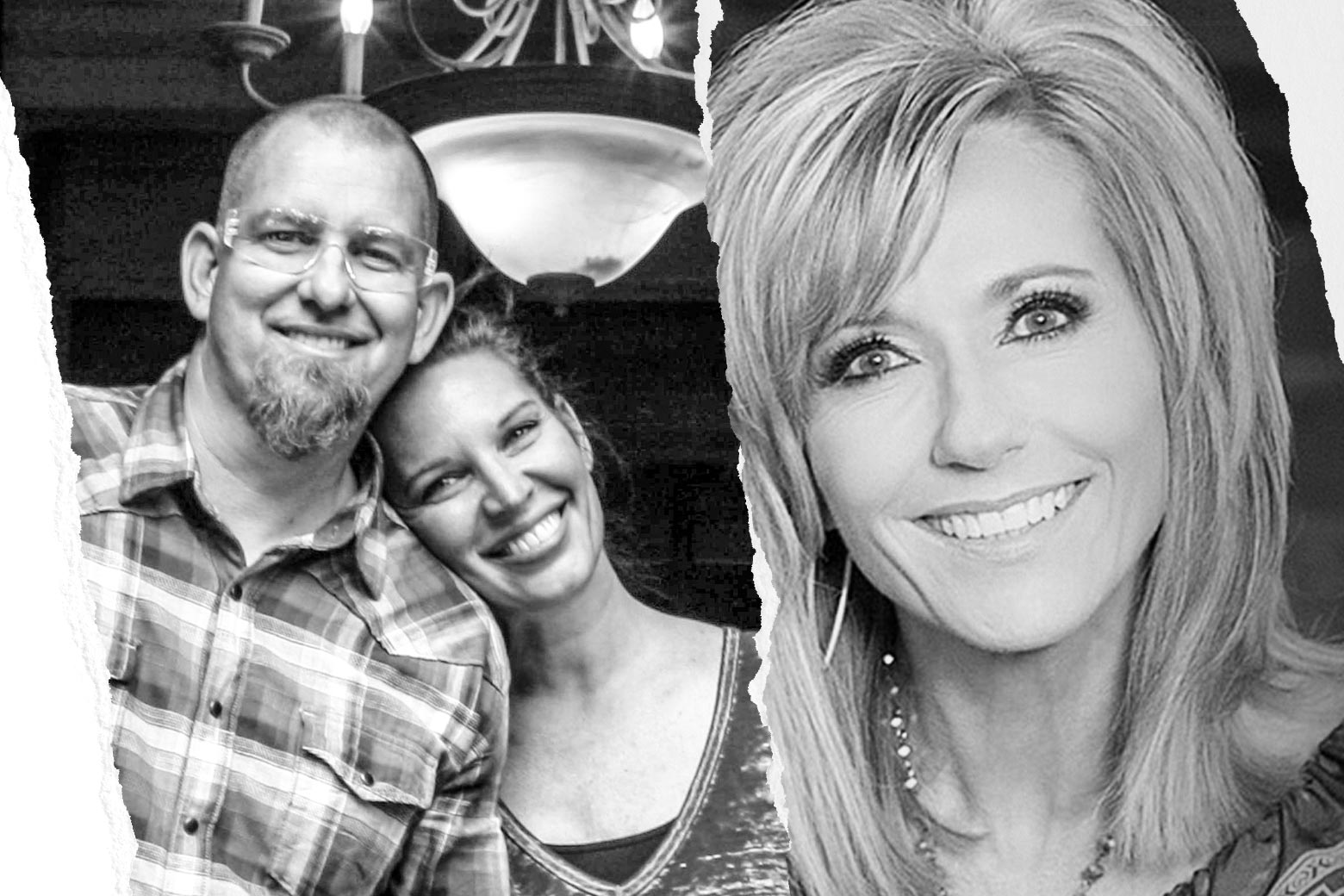

Or their hair isn’t blond, or it’s too short, or they’re overweight, or any of the other things that break the rules. I have asked many women about the awkwardness of that role. There are few examples where women opt out altogether, and then they hire somebody else to run the women’s ministry. But it is not common. It is one of the only remaining professions that is considered a two-person job, but they will never pay one of them.

The only similar job I can think of is being first lady of the United States.

Can you imagine if she was just like, “I don’t feel like it. Not into it.” One of my favorite examples is [Tennessee megachurch pastor] Joseph Walker and [his wife] Stephanie Walker. They had to write an entire book called Becoming a Couple of Destiny in which she had to defend keeping her job as a high-level doctor at Vanderbilt.

You trace how in the early and mid-20th century women like Elisabeth Elliot often became famous for writing missionary memoirs about their adventures overseas. Today, female evangelical celebrities are either pastors’ wives or go out of their way to portray themselves as average wives and mothers. How did those idealized celebrity roles become so narrow?

Missionary agencies offered women this tremendous authority to have global roles as teachers, doctors, and nurses in countries where there either weren’t enough male doctors or there was a significant women-and-children demographic. These women were scrappy, often single, and not always pretty—which I say with great respect.

A number of things happened to women’s missionary agencies. One was that male institutional figures largely took over those budgets from the women who once ran them, cutting out that power source. And as evangelicalism became a cultural force, it marked its difference from the wider culture by lionizing the family. There was less and less desire to see women scrapping it out in the wilderness of Siberia and more of a desire to see her being a Godly mother and a faithful wife.

And at some point the “normal wives and moms” start not just emphasizing their average-ness but start really playing up their own flaws and failings.

You get celebrities who primarily advertise themselves as being “messy” and “broken,” who know how to let Jesus take their junk and turn it into gold. It’s a little hard to believe, often when they’re also simultaneously paragons of the upper middle class. They can only say they were lightly flawed. No one is going to be like, “Well, I was a heroin addict and I still am today.”

You might reveal if you were a heroin addict 20 years ago, right?

This is a question of privilege. When you’re on this pedestal, you can only give a little bit away. You can only share a few of your struggles without taking yourself off the pedestal altogether. This is the politics of respectability that are most obvious when you look at how black women and white women can afford to use that currency. If black women describe their flaws in their life, they’re most often kicked off the pedestal forever. There’s a lot more talk of messiness and brokenness among white women.

Why haven’t women in progressive Christian traditions been able to cultivate this informal influence even when they have access to institutional power?

One reason is that we are snobs. I’m saying “we,” because I’m working in a flagship mainline seminary institution. We think that cheap paperbacks and accessible prose are beneath us. We think that “celebrity” and “brand” are bad words, and we are deeply condescending to people who succeed in them. I think it’s just part of the prestige economy in which we traffic, where we also have a narrow script for what constitutes serious work.

You’re an academic, and you also wrote a memoir about your diagnosis with stage 4 colon cancer, the bestselling Everything Happens for a Reason: And Other Lies I’ve Loved. Did working on this new book affect the way that you thought about your own self-presentation in Christian spaces, as someone with credentials but also with a powerful personal story?

Absolutely. That made part of me deeply resentful. It was hard to hear people want to commodify pain that seemed too easily bought. On the other hand, I realized that there is also such a hunger to know people beyond their self-presentation. One of the biggest buzzwords right now is “authenticity,” because it’s so hard to determine what’s reality and what’s counterfeit.

There’s this incredible moment in the book where you jokingly ask a young speaker how many tragedies she could hope for over the course of her life, to maintain her career, and she says very matter-of-factly, “Four.”

I think that’s why memoir is such a capricious genre and I think, frankly, deeply sexist, with the way that the industry—all industries—market women’s work. Because women are forced out of most credentialed leadership, they’re forced to endlessly self-disclose or use their experience as their authority. And without evergreen authority, they will always be stuck digging in deeper and deeper into their biography. It’s deeply pernicious if women are not allowed to have other expertise.

What do you think would surprise secular readers who aren’t familiar with this whole economy of Christian women celebrities?

These women are scrappy, they’re self-taught, they were usually discouraged from formal theological education. And they have become wonderfully, widely read and resourceful. People who call themselves Bible teachers are mostly people who were not afforded any of the same education or connection and are so good at it, frankly. They can fill stadiums of people who want to hear them put on a one-woman act about the Gospel of Mark. It shows you both what an appetite audiences have for engaged theological education, and what women can do with charisma and a little determination.

You generated some amazing data on appearances, like the fact that the bigger the church, the more likely the pastor’s wife is to be blond. You also find that women married to pastors who wear jeans to preach have to be skinnier, while women at more old-fashioned churches where the men wear suits have the freedom to be heavier. Why are the expectations of beauty higher in the places that look more informal from the outside?

They’ve decided that the way to win the culture wars is to be media-savvy and to be relevant. So the pastor in the jeans is going to want the graphic T and also to look like a CrossFit enthusiast and his wife is going to be conformed to Instagram standards.

Other cultures, like Southern Baptist culture—I can spot a famous Southern Baptist wife 100 miles away. They have their own separate rules, which have largely been set by the denomination and standards of modesty. They’re playing their own internal game and because of that they haven’t bought into the, I think, very toxic beauty culture of the mainstream.

The women you’re writing about attain stature by who they marry. They perform deference to men even if they are popular in their own right. They downplay their credentials. So I sometimes find myself feeling smug when I read about these women. But what does that kind of knee-jerk judgment miss?

The preacher’s wife role is only a slightly exaggerated form of the roles that women are taught to play everywhere. And I mean, barely. Who’s the newscaster and who just does color commentary? Who’s considered serious and who just adds the peppy anecdote? Who’s the president and who does the platform on bullying? This is a culture of Melanias and of borrowed power.

The Preacher’s Wife: The Precarious Power of Evangelical Women Celebrities

By Kate Bowler. Princeton University Press.

Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

Researching this book did help me understand how deeply that I had accepted some of the deeply misogynistic scripts around this, like: I’m a professor, but I’m “just Kate,” because it does make people uncomfortable if you lead with Dr. So-and-So. Breaking the script is hard for all of us, and these women are really doing it. They’re just not asking for their labels to be changed before they do it.

I was really sick when I wrote this book and a lot of the people … it makes me so emotional to think about it. A lot of the people I interviewed were kind and pastoral to me in a way that I probably didn’t deserve. I was taking up their time to ask overly aggressive questions about subjects they’d rather avoid, and they were real pastors. I really came to admire a lot of them as being pretty gutsy.